In 1999, just one year after Tommy and I had married, I convinced him to move with me to a small town 40 miles west of the city. Although Tommy was a lifelong Chicagoan, he agreed, imagining I suppose, that he’d spend his retirement years puttering in a country garden. Alas, my new spouse was unaware he had wed a serial mover, and in less than a year he’d be uprooted and replanted back in the city.

Perhaps I should have confessed – told him the house on Henderson St. in Chicago’s Lakeview neighborhood where I was living when we first met was my 12th residence since my first marriage in 1960. (A few houses and favorite places are pictured in this post and identified at the end.) But honestly, I had thought my moving days were over, filed away with my divorce papers, so there was no need to share my secret addiction.

I had pinned a few of those dozen moves to natural causes; i.e., the army, a growing family, first husband’s new career. As for the rest of our family’s moves, my theories included: empty nest syndrome, projects to recharge a long union, and my short attention span. But, no real answer. Now, though, thanks to a report I found on the Internet, I can blame my grandparents (aka Bubbie and Zadie), and the immigrant roots unearthed in my memoir, “The Division Street Princess.”

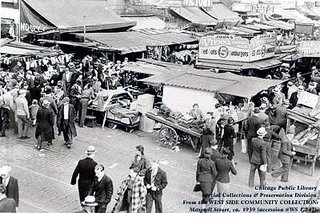

You see, according to Dr. Fred Goodwin, a psychiatrist and former director of the National Institute for Mental Health, ”Some 40 million Americans move every year. We’re a country of movers,” he said. “It’s as American as apple pie.” In an August 5, 2001 interview with CNN, Dr. Goodwin suggested that while some in the same situation stayed behind, “many of our forbearers bravely left their own country, old language, to better their circumstances or avoid religious persecution. The immigrants that came to this country were the risk-takers, explorers,” he said.

Could I have inherited this tendency to courageously seek new vistas from the Shapiros and Elkins who left their Russian shtetls for the concrete streets of Humboldt Park? Although my excuses for 14 homes (last count) have been paltry in comparison to my ancestors’ voyages from Russia to the U.S. in the 1920s, it’s clearly their fault Bradke Movers has been on my speed dial.

As I review my list of addresses, surely the strangest was that 1999 move to Geneva, IL. with Tommy. What possessed me to obscure the Yiddish of my childhood for the Swedish of the Fox River Valley? How could I ignore my liberal Democratic leanings (not to mention my tattooed biceps) to settle in a town almost totally Republican and conservative?

The excuse I gave Tommy at the time was that I wanted to see trees before I died. But looking back, I think I believed my narrow city row house too small to accommodate my new marriage and my two daughters who would occasionally visit from Boston and Los Angeles. A spacious home in the country – certainly more affordable than a similarly sized one in the city –could provide ample room for all.

My friends and family scoffed, taking bets on how long I would last. “If it doesn’t work out,” I told them, “I can always move back.” Tommy -- still unaware of my addiction, but knowing my talent for organization would ease the move and quickly find us new friends and activities – was optimistic.

My spouse was right: the move to a 50-year-old house on a half-acre of land with giant trees and wildflower garden, across the road from wooded trails, and walking distance from the train station, was a breeze. Within days, we joined the Delnor-Community Health and Wellness Center. Tommy planted a vegetable garden, and discovered enough golf courses to keep him puttering and putting. I became a member of the St. Charles Library Writing Group, as well as of Congregation Beth Shalom in Naperville. For a time, I was content.

But to keep a link to the city, and to attend Weight Watchers’ meetings with my old group, I’d climb aboard the Union Pacific/West Line’s 7:25 a.m. to Chicago once or twice a week. And each time the train pulled into the Ogilvie Transportation Center, and downtown skyscrapers magically blossomed before my eyes, I could feel my heart tug for the city I had carelessly forsaken.

Ten months after our move to Geneva, I pleaded with Tommy. “I have to move back.” “You’re nuts,” he diagnosed. Too late. On August 10 (my birthday), 2000, we waved goodbye to Graham’s Chocolate shop, to The Little Traveler, to charming Third Street, to the great group of writers who encouraged my memoir, to the women I met while exercising or praying, and to the other places and people who tried to woo me to beautiful Kane County.

Surprisingly, even though I really was fish out of water, that wasn’t my reason for returning to the city. Folks in Geneva were genuinely friendly, and curious about my pursuits and me. I never felt unwelcome. It was Chicago, the home of my birth, that I missed. Certainly Geneva possessed the trees I thought I needed, and tranquility and charm I believed to be a bonus. But I never realized how much the city’s vitality and variety meant to me. At the end, my twice-weekly Metra visits only stoked, not satisfied my need for tumult, a longing likely sown in Eastern Europe and nurtured on the streets of my childhood.

In January of this year, Tommy and I marked our eighth year of marriage and in August, our sixth year in our home in Chicago’s Independence Park neighborhood. Trees abound in the namesake park across the street. A mix of neighbors stop by our wide front porch to pet our dog and trade news. Tommy tends the backyard flower and vegetable garden when he’s not golfing or bowling. Tommy renewed his YMCA membership; I returned to the East Bank Club. I take the Blue Line to the Loop to window shop and wander.

Tommy warns me that the only way I’ll move from this house is “feet first.” I’m sure he doesn’t mean it, but if the urge should strike, I can honestly say I’m innocent. “It’s in my DNA,” I’ll insist. “Blame those adventurous peasants from the old country. Unwilling to stay put, hungry for the taste of new cuisine, the smell of fresh paint and untreated wood, the sound of hammers and saws, the feel of bubble wrap and corrugated boxes, the sight of blueprints and floor plans. Don’t look at me.”

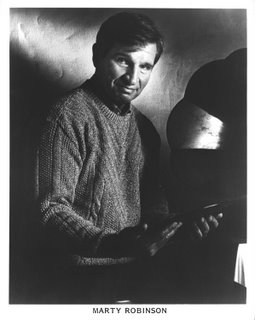

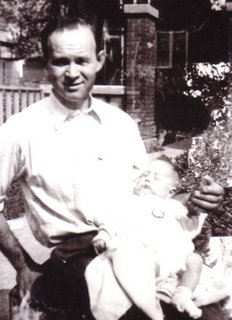

Photo Captions:

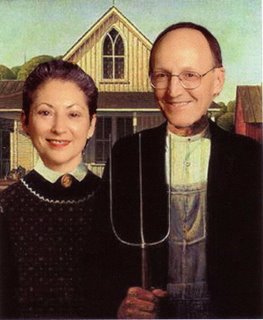

1. Tommy and I pictured in 1999 on a card announcing our move to the country.

2. The Henderson St. row house, which we left for Geneva.

3. Officer’s quarters in Ft. Devens, MA.

4. A first marriage townhouse on LaSalle St.

5. One of my favorite homes, on Maud St.

6. Our Geneva home on Fargo Blvd.

7. The Little Traveler, on Third St., Geneva

8. My office within a Michigan Ave. high-rise condo.

9. Grahams Chocolate shop, on Third St., Geneva.

10. The Independence Park field house.

11. Our current Chicago home with our golden retriever, Buddy, on the front porch.

12. Some of our neighbors posing at a recent block party, which is held annually to welcome new neighbors. Tommy and I were the year 2000 guests of honor.

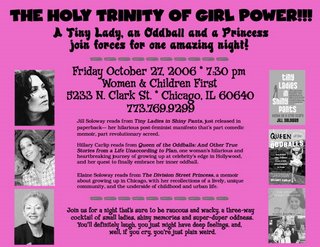

Postscript:

Fans of Chicago history and old neighborhoods should check out "The Pied Piper of South Shore, Toys and Tragedy in Chicago" by Caryn Lazar Amster, a fascinating true crime story set in the 1950s and 1960s. To subscribe to "South Shore News," Caryn's free monthly e-mail newsletter, write to her at: Caryn Amster