Today, at 4’9” (formerly 4’11”), I’m at peace with my stature, and even a bit haughty, thanks to the Short Persons Support website. It was there I discovered celebrity compatriots, as well as advantages. Are you aware my petite pals and I are less likely to break bones in falling or die in auto crashes, and that we live longer than tall people and even benefit the environment by taking up less water, energy, and space?

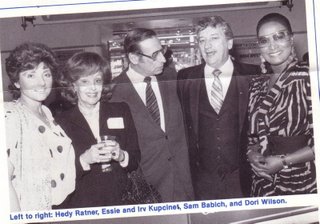

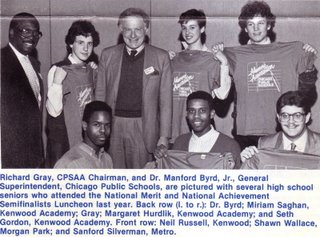

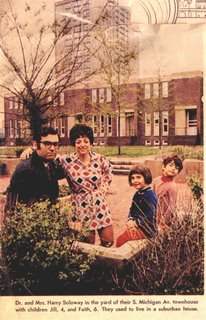

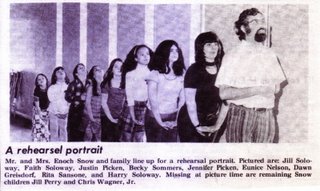

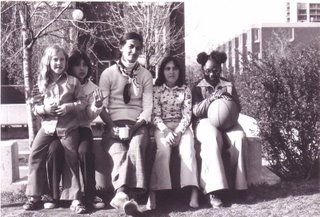

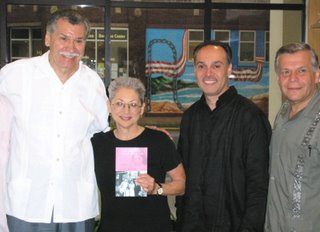

For a clear picture of where I stand compared to others, I’ve included some photos of me in the midst of friends and family. Also, I’ve adorned this post with a few well-known short persons. See if you can identify them -- or peek at the photo captions provided at the end.

In truth, I’ve never felt handicapped as a short woman. Yes, I do have to sit on a child’s booster seat to get my hair shampooed, and I have a hard time at the movies if someone longish fills the seat in front. And at the Jewel, I have to call on taller customers to pick Fiber One off the top shelf. But compared to other possible flaws, my lack of height is a yawn.

In fact my skimpy inches have been an advantage in one area: romance. I never had a problem attracting males, especially the short ones. In high school, any lad who had not attained full height by freshman year, sought me out. And in between my two marriages, when I was divorced and available, my height once more became a magnet, winning me all blind dates under 5’8”. “I’ve got the perfect guy for you,” a friend would say and I knew what she meant. And when I ran ads in the Chicago Reader noting my height along with my religion, love of dogs, jazz, and WBEZ, you can guess what pulled them in.

As I recall, there were merely two work-related incidents where my size caused me grief. The first was in 1980 when I was a press aide for Chicago Mayor, Jane M. Byrne. I was stationed at a ceremonial event -- some ribbon cutting or unveiling -- and along with distributing press kits I was to fend off the glut of reporters who typically pounced on the diminutive mayor the moment she stepped from her limo.

I took my usual stance: both arms extended out to my sides (like a lower case “t”) trying to hold back the crowd of reporters while opening a path auto to dais. But I was a hopeless as the kid with his finger in the dike: Nothing, especially this pint-sized press aide, could stop the rush. Television cameramen, photographers, reporters with their microphones thrust before them, easily pushed me aside and flooded the Mayor. Afterwards, back at City Hall, I overheard Her Honor tell Steve Crews, the press secretary at the time, “Don’t send Elaine to events anymore. She can’t handle it.” I didn’t blame the mayor; she was right.

It took 20 more years for my height to once again affect job performance. I had retired from my city post and public relations career and took a seasonal job at the Gap -- for a kick, for the discount. Denims there were stacked to the ceiling: classic, boot cut, wide leg. Size 2 all the way up to 14. Thousands of blue jeans piled one on top of another. If my customer was a tiny 2, no problem, but anything heftier, and I had to turn to another salesclerk or customer. “Could you please, would you mind?” I would gesture helplessly. And with a chuckle, they would comply.

Admittedly, my height, and lack thereof, has been a recurring theme in my life – sparked I’m certain by my beautiful mother’s concern about her only daughter’s chance at happiness considering a lack of inches from top to bottom and a few excess ones ‘round the middle. Here’s a small bit, skimmed from a chapter in "The Division Street Princess" that proves my point. While I am in the bedroom I share with my sleeping brother, Ronnie, I overhear this conversation taking place in the living room:

“I think we should take her to see someone.” It was my mother talking.

“You’re nuts,” Dad said.

“She’s the smallest girl in her class,” Mother said. “Maybe there’s something wrong that a doctor can fix.” From your lips to God’s ears I thought, repeating a Yiddish expression I had often heard my mother say.

“There’s nothing wrong with her. She’s perfect the way she is,” Dad said. His rebuttal didn’t surprise me for we were a family of shorties: Neither he nor my mother reached 5’5”, my 12-year-old brother Ronnie was short for his age; and I -- my father’s princess -- was the runt of the litter.

I lifted myself on my elbows the better to hear the rest of their conversation. Surprisingly, I was rooting for Mother. If a doctor could fix me up, give me a pill to make me taller, like the rest of my classmates, maybe then people would stop patting me on the head as if I was a pet. Whenever I saw a palm headed for my crown, I’d duck and steer the hand away. I wanted so much to be normal size, not this midget who gets lost in a crowd. Not this baby who has to sit on the Yellow Pages to reach the kitchen table. Not this dwarf perched at a classroom desk, feet never touching the floor.

I fell asleep before I knew who won the evening’s skirmish, but by morning I learned Mom was victorious. Yea! I thought to myself, the doctor will give me some magic pills and I will grow tall, slim, and beautiful.

***

“Well,” the doctor said to my mother as we sat in the examining room, “she is shorter than her age group, but her weight is just right. According to the intake sheet you filled out, I see that you, your husband, and your son are short people. It’s unlikely your daughter will grow much taller than either one of you. I don’t recommend hormone injections at this time.”

Mother turned to me, took my face in her two hands, kissed my forehead, and said to me loud enough for the departing physician to hear, “I knew you were perfect just the way you were.” I was happy to get her kiss and hear her sugary words. But in my heart I knew Mother’s efforts to transform her only daughter were far from over -- just temporarily stalled.”

Photo Captions

*School photo: First seat, first row, on the right. Feet in dark socks not reaching the floor.

*Edith Piaf, 4’8”

*Women and Children First Bookstore, May 25, 2006: Cousins Neil Shapiro and Renee Elkin on either end, my brother Ron on one side and my daughters Jill and Faith on the other. Note that my grandson is quickly catching up.

*Donna E. Shalala, 4’9”

*At the Teresa Roldan Apartments on Paseo Boricua, July 20, 2006: With Paul Roldan, Ald. Billy Ocasio, and Jose E. Lopez.

*Robert B. Reich, 4’10.5”

*Borders, Los Angeles, July 25, 2006: With Romie Angelich, Melanie Hutsell, and daughter Jill Soloway.

*Judy Garland, 4’11.5”